Kate Formico’s Family Tree Is A Who’s Who Of Accomplished Athletes — And She Definitely Belongs.

Story by DAVID KIEFER | Photos by NORBERT VON DER GROEBEN

When Kate Formico unwinds, she grabs a volleyball.

When she was younger, Kate used the outside wall under the kitchen window to set, serve, and spike the ball off of. The thumping became a regular sound in the family symphony. However, now the wall is off limits, as a precaution from a cave-in.

The present target is a backyard backboard. The ceaseless pounding against it, and the feel of the ball against her fingers keeps Kate from getting bored. The sport is never a chore.

“I just love to play volleyball,” Formico said.

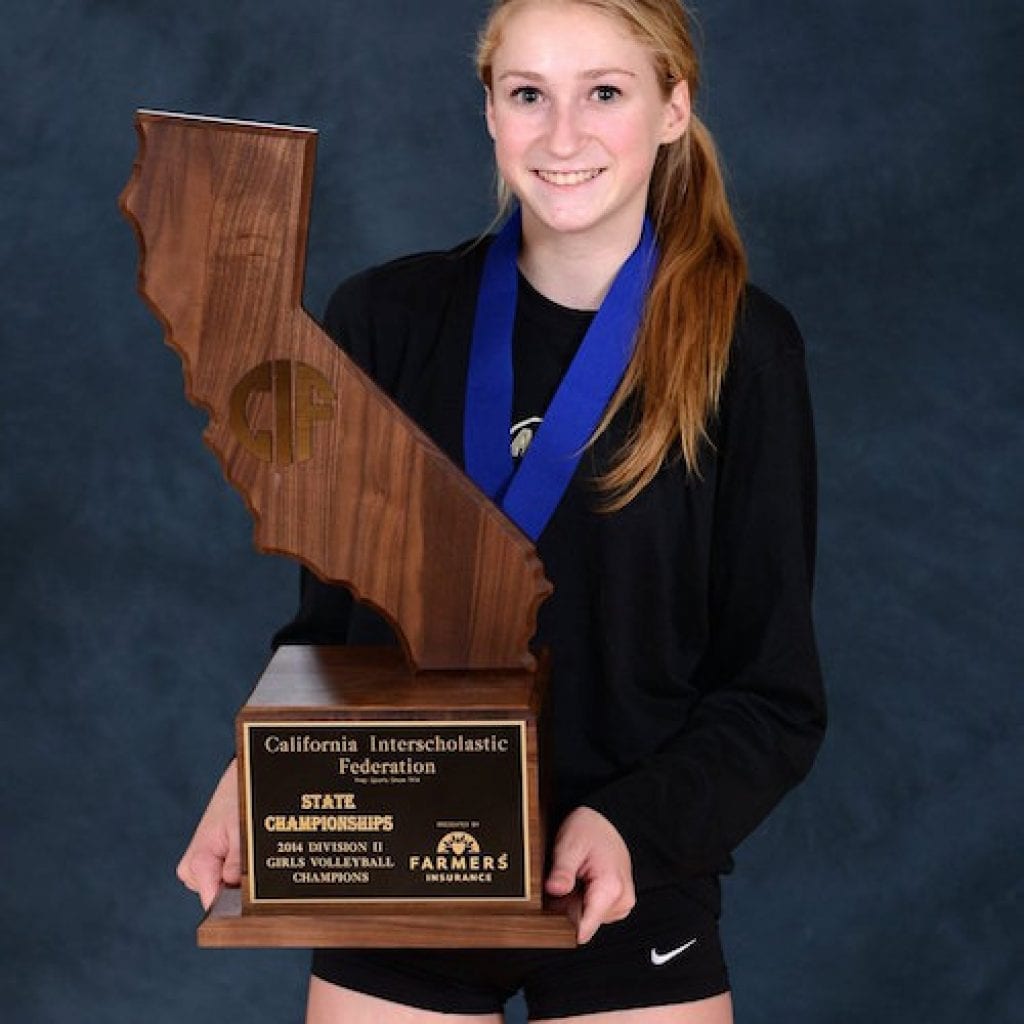

Formico is one of the top volleyball players in the Bay Area, and beyond. She has been an integral part of two state championship teams at San Jose’s Archbishop Mitty High School, and is among the best young beach players in the country.

But despite the time and devotion she puts toward the game, there’s no questioning its value. It’s part of her DNA.

Kate’s first cousin is Kerri Walsh Jennings, perhaps the most recognizable volleyball player on the planet. Walsh Jennings, now 37 and a Mitty grad, has won three Olympic beach volleyball gold medals and will be competing for her fourth in Rio.

But when asked about role models, Formico said that they go far beyond just Kerri. A glance at her family tree explains why.

Let’s start with Marte Formico II, the Abraham of this clan. Marte was a star during the heyday of Santa Clara University football, when the Broncos beat Bear Bryant’s Kentucky in the 1950 Orange Bowl. Formico was inducted into the SCU Hall of Fame in 1984.

Formico wasn’t very big – one report had him under 140 pounds – but he was an elusive back. Teammates called him, ‘Splendid Splinter,’ a nickname originally bestowed on baseball star Ted Williams. While the origins of Williams’ nickname are unclear, for Marte Formico, his nickname started “because he wasn’t any bigger than a splinter,” said one teammate.

Well, Marte begat eight children, all with first names starting with ‘M,” including Margie, who begat volleyball-playing sisters Kerri, K.C., and Kelli. Among Margie’s siblings are Maureen Formico, Pepperdine’s all-time leading scorer in basketball, and Kate’s dad, Marte III. There actually is a Marte IV, Kate’s brother who starred in soccer at San Jose’s Bellarmine College Prep and was regarded as the Central Coast Section’s best player. He will play at UC Davis this fall.

Among their cousins are UCLA volleyball star Taylor Formico, the Pac-12 Libero of the Year last fall, former University of Arizona libero Ronni Lewis, and Joan Caloairo, who played setter at University of San Francisco and Cal.

More cousins: Marcia Wallis, an All-America in both soccer and golf at Stanford, Brian Bernard, formerly of the U.S. national rugby team, and Angelo Caloiaro, who plays professional basketball in Turkey.

“How do you explain it?” Mitty coach Bret Almazan-Cezar said. “It’s their culture. They are going to compete and do their best.”

Family athletic success can have its pros and cons. On one side, there can be pressure to live up to the achievements of others, and that may be magnified with a three-time Olympic gold medalist attending to the same family barbecues. There also can be the false assumption that talent is God-given, rather than the product of hard work.

On the other side, there seem to be standards in focus, preparation, and competitiveness that already are long established in the family and can hardly be taught.

“She reads the game better than anyone we’ve ever had,” Almazan-Cezar said, “with the exception of Kerri.”

Kate is a 5-foot-9 libero, who is superb defensively, an adroit passer, and has proven on the beach that she can hit. But her primary skills are on defense. Formico’s familiarity with the game, and understanding of it, pay off in her ability to know where the set is going and how to anticipate where a swing is coming from.

“I watch the hitter’s arm,” Formico said. “I’ll watch them in the hitting lineup or during the game. You watch their swing and try to pick up different tendencies. Maybe they like to hit it down or to the deep corner. You can pick up a lot that helps you during a game.”

For some players, the excitement of a big hit is what motivates them. But for Formico, it’s the opposite: “I love digging,” she said. “The best thing is to dig a ball against a big hitter.”

Almazan-Cezar’s praise of Formico is high considering he has coached Mitty to 15 Central Coast Section championships in 23 years and has had great liberos, such as Lewis and Anne Marie Schmidt, now at USC.

Formico’s defense is only part of the reason Mitty doesn’t have to concern itself with a good portion of the court defensively. The other is Formico’s passing skills. Almazan-Cezar likens Formico to a shutdown cornerback in football. Opponents don’t want to serve to Formico and limit their serving to smaller areas, making it easier for Mitty to cover, allowing Mitty to more easily transition into its offense.

“We know we can take 2/3 of the court away on serve-receive because of Kate,” Almazan-Cezar said.

But Formico also gives Mitty an advantage partly because of the skills she has honed on the beach, where only two players must cover half a court – as opposed to six-a-side indoors. The demands of the beach make her quicker and more mobile. And the constantly pushing and jumping off sand has made her legs all that much stronger.

Almazan-Cezar said that when Formico was a freshman, she reminded him of a “mini-Kerri.” She had the same tall lean athletic build along with a quiet yet driven personality.

The drive manifests itself in her unquestioning desire to trust her coaches and do whatever they ask.

“Kate never has an excuse,” said Jen Agresti, Formico’s coach with the Encore club team. “If you talk about strategies or defensive systems, she puts her head down and wants to go. Mentally, she’s at a different level.”

While the naturally-shy Walsh found her voice, so must Formico. Mitty lost seven seniors from a program that won its fourth consecutive state title and 12th overall. She is one of three seniors and perhaps the most prominent.

She knows her leadership will be vital toward a fifth consecutive state title run and that her encouragement or blessing can go a long way in the development of the Monarch’s newcomers.

“At the beginning of the season, my role will be really big,” Formico said. “I’d love to teach them the ways we do things, and to stay positive. It should be a fun year. I expect great things for Mitty. Everyone still expects us to do well.”

Almazan-Cezar likened Formico’s leadership to her play.

“She’s very steady, she’s very calm, and she’s very present,” he said. “She doesn’t look to be flashy, but Kate always seems to be where the ball is.”

With the growth of beach volleyball as an NCAA-sponsored scholarship sport, players now have the option to play one or the other, or both.

Formico isn’t ready to make a commitment, to a season or a school. She can see different scenarios, but likely will stay on the West Coast.

Walsh Jennings continues to be an inspiration, especially as she attempts to capture her fourth Olympic gold medal.

“Kerri is my role model on the beach,” Formico said. “But I love to watch all my cousins play.”

Despite a crowded family tree, there definitely seems to be room for at least one more volleyball star in the family.

[bsa_pro_ad_space id=22]